Class III malocclusion is one of the most recognizable bite problems in dentistry, but also one of the most challenging to manage. While it is easy to spot clinically, achieving a stable and esthetic correction requires a deep understanding of the underlying skeletal and dental components.

In this article, we break down what Class III malocclusion is, why it develops, and how orthodontists today approach treatment at different ages.

What Is a Class III Malocclusion?

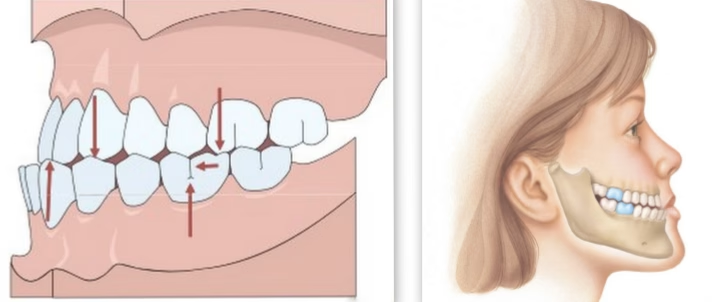

A Class III malocclusion, often called an “underbite”, happens when the lower teeth and jaw sit in front of the upper teeth. Some people have a mild underbite, while others have a more noticeable one that affects their smile, chewing, and confidence.

People with Class III often show:

- An underbite (lower front teeth in front of the upper front teeth)

- A concave facial profile (the middle of the face looks a little flatter, the chin more prominent)

- A jaw that looks “stronger” or more forward

- Sometimes difficulty chewing or biting into foods

How Common Is Class III Malocclusion?

Class III malocclusion is the least common of the Angle classifications.

- Normal occlusion: ~30%

- Class I malocclusion: 50–55%

- Class II malocclusion: ~15%

- Class III malocclusion: <1%

There are also significant ethnic variations:

- More common in Asian populations.

- Also more common in individuals of African descent.

- Less common in Caucasians of northern European origin.

Why Does Class III Malocclusion Happen?

Class III bite problems arise from one or more of the following:

1. Pseudo Class III

A functional, not skeletal, problem. This occurs when the child shifts their mandible forward to avoid their front incisors from touching eachother when they chew.

Often caused by:

- Premature occlusal contacts

- Lingually erupted maxillary incisors

- Maxilla and mandible of similar width

- Retained primary incisors altering eruption paths

2. Skeletal Class III

A true skeletal discrepancy, typically involving:

- Small or retrusive maxilla

- Large or protrusive mandible

- Combination of both

Cephalometric features may include:

- Small SNA

- Large SNB

- ANB ≤ 1°

- Proclined upper incisors and retroclined lower incisors as natural compensations

Treatment Options

Treatment depends heavily on age, growth potential, and whether the problem is dental, functional, or skeletal.

1. Treating Pseudo Class III

The goal is to eliminate the functional shift and correct the anterior crossbite.

Options include:

- Removable appliances with advancement screws or finger springs

- Sectional braces to tip maxillary incisors forward

Why early correction is important:

Untreated functional shifts can lead to:

- TMJ remodeling changes

- Asymmetric growth

- Incisor wear

- Gingival recession

- Muscle hyperactivity on one side

2. Growth Modification for Skeletal Class III

Effective only when the child is still growing (ideally ages 6–10).

Protraction Headgear (Facemask)

Often paired with rapid palatal expansion (RPE).

Expected outcomes:

- Maxilla moves forward and downward

- Mandible rotates downward and backward

- Upper incisors advance 1–4 mm

- Lower facial height increases

Best results occur when treatment starts early, before the pubertal growth spurt.

3. Camouflage Treatment

Appropriate for mild skeletal Class III cases after growth completion.

Goal: Improve tooth alignment while accepting underlying skeletal discrepancy.

Approaches:

- Class III elastics

- Interproximal reduction of lower incisors

- Strategic extractions (e.g., upper 5s and lower 4s)

- Retroclining lowers and proclining uppers within safe limits

- Upper proclination ≤ 120°

- Lower retroclination ≥ 80°

Best outcomes occur when:

- Soft tissues are favorable

- Lower facial height is normal or reduced

- There’s minimal crowding or dental compensation

Poor candidates include:

- Large skeletal discrepancies

- Significant asymmetry

- Large lower facial height

- Severe crowding

- ANB < –4°

4. Orthognathic Surgery

Indicated for moderate to severe skeletal Class III once growth is complete.

Surgical options:

- Maxillary advancement

- Mandibular setback

- Bimaxillary surgery (most common)

Typical treatment sequence:

- Pre-surgical orthodontics to decompensate

- Surgery to correct skeletal discrepancy

- Post-surgical orthodontics for detailing

Surgery addresses both the functional and esthetic consequences of Class III malocclusion.

Key Treatment Planning Considerations

When determining the right approach, clinicians evaluate:

- Degree of AP and vertical discrepancy

- Growth status and future growth potential

- Facial profile

- Incisor angulation

- Overjet/overbite

- Presence of functional shifts

- Crowding

- Ability to achieve edge-to-edge incisor position

Final Thoughts

Class III malocclusion is complex and multifactorial, but modern orthodontics offers a wide range of effective strategies — from simple early interceptive treatments to advanced surgical corrections.

The key is accurate diagnosis, early intervention when appropriate, and a personalized plan that considers growth, facial esthetics, and long-term stability.

Disclaimer

The contents of this website, such as text, graphics, images, and other material are for informational purposes only and are not intended to be substituted for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Nothing on this website constitutes the practice of medicine, law or any other regulated profession.

No two mouths are the same, and each oral situation is unique. As such, it isn’t possible to give comprehensive advice or diagnose oral conditions based on articles alone. The best way to ensure you’re getting the best dental care possible is to visit a dentist in person for an examination and consultation.

SAVE TIME AND MONEY AT ANY DENTIST

Less dental work is healthier for you. Learn what you can do to minimize the cost of dental procedures and avoid the dentist altogether!