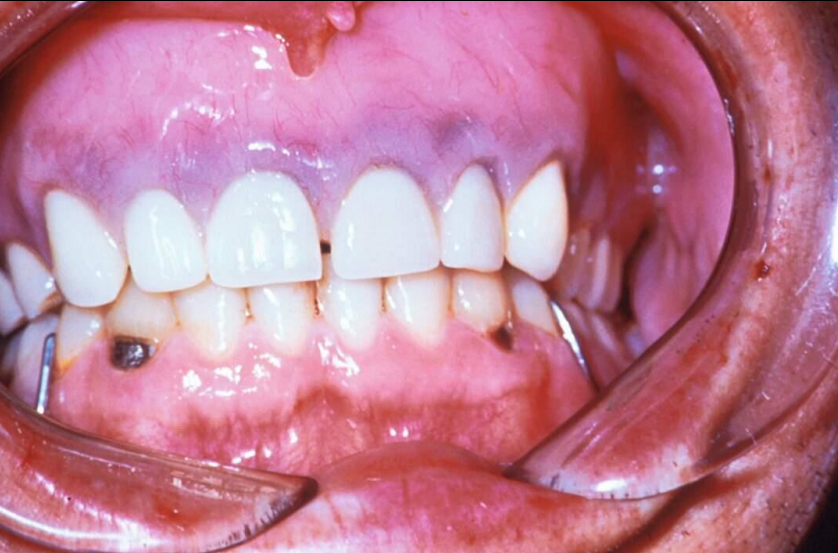

Class I malocclusion is the most common orthodontic problem. Unlike Class II (“overbite”) or Class III (“underbite”), Class I malocclusion has a normal molar relationship but features issues such as crowding, rotations, or crossbites.

This makes it a unique condition: the bite may look “normal” at first glance, but the details reveal functional and esthetic challenges.

What Does a Normal Bite Look Like?

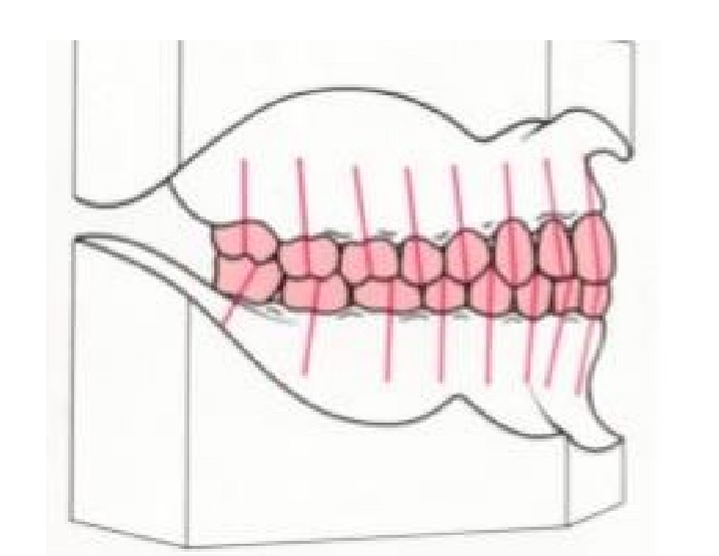

In dentsitry we call the ideal bite Class I Occlusion. In a healthy Class I occlusion:

- The mesiobuccal cusp (the front outside point) of the upper first molar fits neatly into the buccal groove (a natural depression) of the lower first molar.

- The teeth have the proper angulation (the tilt of a tooth when viewed from the front) and inclination (the forward or backward tilt when viewed from the side).

- There are no rotations (teeth turned out of place).

- The curve of Spee (the natural curve formed by the biting surfaces of the teeth) is relatively flat, with a shallow depth.

This alignment allows for efficient chewing, speech, and long-term stability of the dentition.

What Is Class I Malocclusion?

In Class I malocclusion, the back teeth (molars) are aligned normally, but the front or side teeth are not. The condition may include:

- Crowding: insufficient space in the jaw, causing teeth to overlap.

- Rotations: teeth turned or twisted out of alignment.

- Overbite variations: either too much vertical overlap of the upper front teeth (deep bite) or too little (open bite).

- Crossbites: upper teeth biting inside lower teeth instead of outside.

The skeletal base (the underlying jaw structure) is usually Class I (which is considered ideal), though mild Class II (upper jaw forward) or Class III (lower jaw forward) tendencies can also be present.

Why Does It Happen?

The most common cause is dentoalveolar disproportion — a mismatch between the size of the teeth and the available jaw space. Other causes include:

- Genetics (large teeth from one parent, small jaws from the other)

- Early loss of baby teeth, which allows neighboring teeth to drift and block space

- Oral habits such as thumb sucking or tongue thrusting

- Minor discrepancies in jaw growth (slight skeletal imbalances)

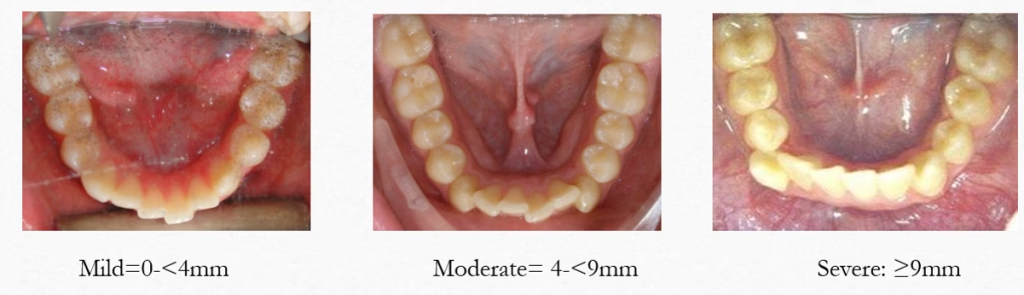

Diagnosing Class I Malocclusion

1. Clinical Assessment

Dentists first estimate the amount of crowding:

- Mild: less than 4 millimeters of space shortage

- Moderate: 4–9 millimeters

- Severe: more than 9 millimeters

Here, “millimeters” refer to the gap between the amount of space available in the dental arch and the total width of the teeth that need to fit into it.

2. Model Analysis

Dental casts (or digital scans) help quantify space discrepancies:

- Carey’s Analysis compares tooth size to arch length.

- Howe’s Analysis compares tooth size to the width of the jaw bone.

- Bolton’s Analysis measures proportional differences between the upper and lower teeth.

3. Cephalometric Analysis

This uses specialized side-view X-rays to evaluate tooth positions:

- Upper incisor to palatal plane (U1 to PP): normally ~111° (±5).

- Lower incisor to mandibular plane (L1 to MP): normally ~90° (±5).

- Interincisal angle (the angle between upper and lower front teeth): ideally ~130°.

Teeth that are more upright or tilted forward/backward than normal will affect whether extra space is needed or can be gained during treatment.

Treatment Options

Treatment options vary depending on what the cause of class I maloclussion is and what the patient wants to achieve from treatment. In general it can be broken down into three main categories with the following treatment options.

Mild Crowding (<4 mm)

- Proclination: gently tipping the front teeth forward to create more room.

- Interproximal Reduction (IPR): carefully reshaping the sides of teeth to gain small amounts of space (0.5–0.75 mm per contact).

Moderate Crowding (4–9 mm)

- May be managed with or without extractions, depending on tooth inclination, lip support, and gum health.

- If crowding is located more toward the back teeth, extraction of second premolars may be considered.

Severe Crowding (≥9 mm)

- Extractions are almost always required, usually of the first premolars.

- A guiding principle is that extractions should be balanced in both arches to maintain the Class I molar and canine relationships.

Retention After Treatment

After orthodontic correction, teeth tend to drift back toward their original positions. Retention is essential and a lifelong commitment and may involve:

- Hawley Retainer: a removable appliance with a wire and acrylic base.

- Essix Retainer: a clear plastic tray that fits over the teeth.

- Bonded Retainer: a thin wire permanently attached behind the front teeth.

Conclusion

Class I malocclusion is unique because the molars are aligned correctly, yet the teeth can still be significantly crowded, rotated, or misaligned. The severity of the problem — mild, moderate, or severe crowding — determines whether treatment involves minor adjustments, enamel reshaping, or extractions. With proper diagnosis and modern orthodontic techniques, patients can achieve both functional stability and improved esthetics.

Disclaimer

The contents of this website, such as text, graphics, images, and other material are for informational purposes only and are not intended to be substituted for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Nothing on this website constitutes the practice of medicine, law or any other regulated profession.

No two mouths are the same, and each oral situation is unique. As such, it isn’t possible to give comprehensive advice or diagnose oral conditions based on articles alone. The best way to ensure you’re getting the best dental care possible is to visit a dentist in person for an examination and consultation.

SAVE TIME AND MONEY AT ANY DENTIST

Less dental work is healthier for you. Learn what you can do to minimize the cost of dental procedures and avoid the dentist altogether!